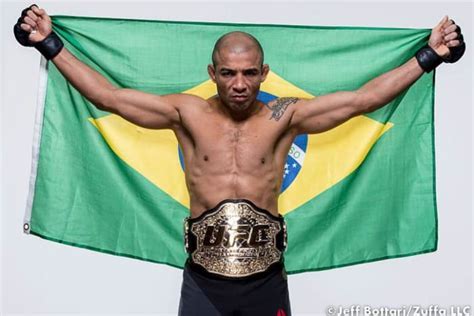

Spend enough time on the internet discussing mixed martial arts, and you will undoubtedly be faced with one of the premier questions in all of sports: who is the greatest of all time? In MMA, a multitude of elite candidates are discussed. Please don’t say Khabib. Typically, the names referenced are Jon Jones, Georges St-Pierre, Anderson Silva, etc. If you hang around the right circles you’ll hear Demetrious Johnson and even Fedor Emelianenko brought up. Recently, newer names like Alexander Volkanovski have been discussed. There is an argument to be made for each of the above, some better than others. The point of this piece is not to debate who the GOAT is. That can be an endless conversation. Instead, I want to show respect to a man whose name is seldom mentioned in this vein, and whom so much of the fanbase is prone to forgetting (looking at you, Mcgregor fanboys). Jose Aldo. The king of Rio. Again, the point of this article is not to bicker about who the greatest is. I will leave that to X and Instagram. Rather, I will be pointing out why Aldo belongs in the conversation, and breaking down a few key elements of what made him so sharp for so long.

Aldo’s career had two main halves. A professional from 2004-2025, he has been fighting most of his life, having just retired earlier this month at the age of 38. Unlike so many with that mileage, Aldo did not experience a sharp decline. His longevity and excellence in the sport for so long are nearly unparalleled. In the first half of his career, encompassing most of his featherweight run, Aldo relied on his athleticism and power to dominate his opponents. His speed and force were too much to handle for the vast majority of his opposition. After a 2005 loss, Aldo went undefeated for his next 18 fights, not facing another defeat until over a decade later to Conor Mcgregor (pre-cocaine). We all know how competitive the lighter weight divisions can be. This is an insane statistic. To go undefeated for over a decade in such a shark tank for the world’s premier organization(s) is GOAT material. Obviously, he lost to Mcgregor in 13 seconds (as a Bills fan, I feel his pain), which discredited him in the eyes of so many. Casuals. Yet, after this crushing defeat, not only did he win his featherweight belt back, but he even found success at bantamweight, finishing the lion’s share of his remaining career there and even challenging for gold at one point. So, to reiterate, after going undefeated for 10 years, he wins another championship, and not only that, but remains a top-tier competitor in a completely different weight class well into his twilight years. Even after his physical prime, Aldo found ways to augment his game, becoming an even better fighter in some respects. Instead of relying on his physical gifts like he did early on at featherweight, at bantamweight, he compensated for his athletic decline by becoming markedly improved technically, tactically and defensively. His evolution and adaptability were a treat to watch. Aldo fought them all. From the days of the WEC before the merger, to the cream of the crop in modern MMA. He was not a relic left behind.

A WEC and two-time UFC featherweight champion, Aldo holds victories over Urijah Faber, Frankie Edgar (twice), Cub Swanson, Chad Mendes (twice), Mike Brown, Korean Zombie, and more. While WEC champion, he was promoted to UFC champion during the merger. He holds victories over ranked opponents at bantamweight, namely Marlon Vera and Rob Font. For those unfamiliar with the WEC, this was no B-league organization. At the time, the talent in organizations like Strikeforce and the WEC could stand tall against the best in the world. Need I remind everyone of how many fighters from both organizations succeeded in the UFC? That’s not to say Aldo remained dominant his whole career. Let’s look at who he lost to, namely Petr Yan, Max Holloway, Volkanovski, and Merab Dvalishvili. Every opponent he lost to after 2005 was either a champion or ranked contender. Aldo has been fighting against the best nearly as long as I have been alive. Those disparaging his name are either rage baiting or uneducated. Now that we have laid out his accolades, let’s delve more into the intricacies of Aldo’s game, and what made him so great.

In his earlier career at featherweight, Aldo was and still remained primarily a striker, despite his black belt in Brazilian jiu jitsu. Reliant on his power and agility, he mainly utilized grappling in a defensive connotation, known for his fantastic takedown defense. We can see Aldo’s style at work in his 2008 fight against Alexandre Franca Nogueira. Aldo exhibits his patented high guard and Muay Thai stance. Never much of a volume fighter, a la Max Holloway, Aldo emphasizes force and precision over accumulation. Even in this early fight, it is clear that he still alters his targets well, ripping both the body and head. Rather than throw elongated combinations, Aldo hones in on timing to land quality blows. Against Nogueira, Aldo had success in avoiding the sting of his opponent’s punches while landing a jab cross, left hook to right cross, and left hook to right hook combinations from the orthodox stance. In particular, this fight was an excellent precursor to the rest of his career in terms of his defensive grappling. Aldo, when facing a single leg takedown in particular, excels in maintaining balance while pushing his opponents head down to weaken their stance, then turning his knee downward to the floor, twisting his body, and ripping the leg out. In wrestling, this is not as effective, as the opponent’s grip catches on the shoe. In MMA, it worked beautifully, for Aldo at least. Aldo defends takedowns in this way across his many years in the game. This was seen in his fights with Mendes and Edgar (both elite wrestlers).

In his fight against Rolando Perez shortly after, we can see another piece of Aldo’s puzzle on display to greater effect, his leg kick. Aldo, a former soccer player, kicked out his opponent’s legs in much the same motion. In those days, the calf kick (popularized by Benson Henderson) was not really utilized. Aldo, at this point, would kick at his opponent’s lead leg, whipping his shin up and in a downwards arc to target just above the knee. He did this early, often, and to great effect. Nobody sniped the lead leg like Aldo. He turned Faber’s leg into mincemeat over the course of five rounds with this same kick, and nearly did the same to Edgar during their first fight, knocking both off their feet multiple times. This compromised his opponent’s mobility, leaving them a sitting duck, and weakened their punches, as they could not use their legs to create force in their strikes. Aldo would often punctuate combinations with leg kicks, using them to create one last bit of damage as he disengaged.

His battle with Mike Brown in 2009 to win the WEC featherweight championship displays another component of Aldo’s takedown defense, that being his fence wrestling. Aldo’s fence wrestling is not perfect, and in his later years made him prone to being held against the cage, not in danger, but immobile. However, it did do the job in that Aldo, like we have referenced, was so rarely taken down in all phases of his career. Fence grabs from time to time played a role, but let’s pretend that didn’t happen. Aldo, against the cage, bladed his stance and would either A: get double underhooks or B: use a whizzer to overhook his opponents arm, then use his opposite arm to frame off of their bicep. Both accomplish the feat of raising his opponent up towards his level, making it more difficult for them to lower their base, lock their hands, and complete the takedown. In particular, Aldo used his whizzer defense at featherweight against Brown, and to great effect against Edgar, though not solely against the fence. Against Edgar, in both fights, as Edgar would shoot, Aldo would incorporate an overhook while pushing his opponent’s head down and to the side. This created a shucking motion that sent his opposition flying past him.

Versus Mark Hominick in his UFC debut in 2011, one could see Aldo’s protection against strikes take a leap into the upper echelon. That’s not to say Aldo was a slouch beforehand. Yet, he seemed to consider other options besides his offense being the best defense. Against Hominick, he utilized pivots (we will get more into this), and in particular slips, pulls and rolls. Aldo seemed to like slipping the straight strikes to land crosses, hooks, or combinations as he pivoted out and circled back in. There were numerous instances when Aldo would either slip the jab or pull back from the hook to land his right straight and left hook. He would expand upon this later in his tenure, incorporating shoulder rolls to further enhance his defense. Aldo, in this fight and beyond, would also utilize singular, heavier strikes as he entered range, rather than just a jab. In this Hominick fight, for instance, he would attack with uppercuts or hooks to both the body and head, one at a time.

Additionally, Aldo seemed to favor two weapons when his opponent pressured into his range; that being a knee and uppercut to either target. Whether his opponent was looking to enter the pocket, looking to clinch, or shooting for a takedown, much the same principles applied. Aldo’s uppercut, for instance, was a great close range strike in this scenario, as the target is already on its way in. I found Aldo’s selection of knees more fascinating when facing pressure. The purpose and effect of the defensive knee was threefold. Number one; simply feinting it kept his opponent honest and presented a deterrent, they might think twice about entering his range or attempting a takedown if they knew they faced such a risk. Number two; when timed correctly, the knee was a damaging strike that took the wind out of the other fighter’s sails and stopped their offense in its tracks, while also providing a physical barrier that halted whatever offense they were trying to mount. Number three; a natural reaction to a knee (whether it connects or not) is to pull one’s face away from the danger and get away. This causes the opponent’s head to rise and their stance to square, making it easier for Aldo to press forward and headhunt with straight strikes and hooks. We can observe this early, such as Aldo’s fight with Brown, and all the way to his 2016 rematch with Edgar to earn back featherweight gold. When the opponent tried to level change or pressure into him, Aldo was ready with the knee. Offensively, Aldo favored a variety of knees, which were typically used when his opponent was hurt, retreating, or both. Once Aldo felt that the opponent was suitably softened up by his strikes, he would capitalize with a powerful knee and try to split the guard. We see this, for example, in his highly competitive fight of the year in the 2014 rematch with Chad Mendes, and even in his 2021 bantamweight fight with Font towards the end of his time. As Mendes is hurt by Aldo’s attacks and retreats, Aldo capitalizes with knees, doing nearly exactly the same with the mentioned Font and even Perez back in the 2000s.

As alluded to above, Aldo’s boxing remained one of his greatest strengths. During his first fight with Edgar, we saw him finally utilize and incorporate the jab into his arsenal on a regular basis (Aldo also regularly popped the jab in their second bout). The jab is one of the first things taught in boxing, yet surprisingly few fighters take advantage of it. We never saw Aldo truly take over a fight using the jab alone, but when it was used, it was advantageous and appropriate. The jab was also a keystone species in the fact it is half of the 1-2, an extremely simple combination that coincidentally happens to be one of Aldo’s favorites. Aldo used the jab to land the cross, and this 1-2 was used in too many fights to name, with prime examples being both Edgar fights, Hominick and Font.

Let’s chat more about Aldo’s body work. In addition to his singular body hooks and uppercuts, he was always rather skilled with combinations to this target. In nearly every fight at both weight classes, Aldo at least attempts combinations to the midsection, which can also be used to set up punches to the head. Aldo in certain moments threw a double lead hook (one to the body, one to the head). The body shot caused the opponent to drop their guard, leaving the chin/temple exposed. We can see this happen at least once during his title fight against Yan and during the Pedro Munhoz fight, who was ranked number nine in the world at bantamweight at the time. Very crafty move by Aldo, not often do you see fighters throw the same sort of shot twice in a row. Aldo also attacked with opposite body hooks on a consistent basis, landing with thudding impact. He appeared in favor of the 4-3 (rear to lead hook). This was done ad nauseum versus Mendes the second time around, and during his clinic of a performance against Munhoz as well as his title fight with Yan (the boxing exchanges in the pocket were absolutely gorgeous here). Spamming the 4-3 and 4-3-4 is classic Aldo, and was a cornerstone in his toolkit.

This next one is my favorite to point out. Pivots. Aldo’s best work on both sides of the coin comes from pivots. It’s why he had possibly the best defense in the entire sport. He does not get tagged clean, and this is a key reason as to why. In addition to his slick head movement, Aldo is exceptional at ringcraft, and is often seen circling his opponent away from danger as opposed to laterally or back and forth. When a fighter advances towards Aldo looking to land strikes (typically jabs), Aldo will first reach out his lead arm to create a post, creating a physical obstacle. This is similar to the classic schoolyard bully, placing his hand on your forehead so you can’t reach him. Aldo will then back away from the other combatant at an angle, approaching and skirting the cage. He keeps his right hand up to guard his chin while he does this to provide an extra layer of armor. Upon circling back out from the cage, he has the option to land offense from a favorable angle. For instance, he used this technique against Edgar to land a clean right cross in their first bout. Aldo exhibited this high level defensive maneuver constantly, and it is practical for a variety of reasons. As mentioned, the post creates a first layer of protection that slows the opponent and prevents heavy blows from landing. The backwards angular movement ensures that Aldo is not stationary for too long, while the right hand guards his head to be defensively responsible. Finally, by skirting out from the cage and back out into open space, Aldo is effectively out of danger, avoids being cornered, and has a great avenue to counter should he deem it appropriate. Many fighters operate like they are in a 2-D Gameboy controller, with only forwards, backwards, and side to side controls. This leads to being backed into the fence or tracked down alongside the cage. This is how Volkanovski found himself in trouble against Ilia Topuria, by moving straight backwards. In this circular movement, Aldo can evade attacks while never really running out of real estate. It’s genius, and one can see him molding this defensive craft into nearly every fight except perhaps his very early ones. Aldo’s counter hooks also came off of pivots. While not as elaborate or time consuming as what we just discussed, Aldo loved to slip or roll with a punch in the pocket or otherwise at range, pivot around his opponent, then counter. A true expert in putting his opponent in essentially a washing machine. Geometry has nothing on Jose Aldo.

Since this is already exceeding most folks’ attention spans, let me land this plane by touching on Aldo’s bantamweight run. By this point, Aldo was in the second half of his career. As hinted at early on in this post, Aldo was past his physical prime here. He was not as athletic, and his stamina, which had never been particularly noteworthy, could be a liability as fights dragged into the later rounds. Yet, this is where Aldo was fundamentally at his best. This is why he is an all-time great. Even at this seasoned stage, he was adapting and improving. His strengths became his form and even tighter defense, while still maintaining incredible speed and power. Even in his very last fight he held a speed advantage. Aldo at bantamweight was very similar to featherweight in terms of his habits, he simply improved on them. Same emphasis on pivots, same beautiful work to the body. Just tighter defense, more selective striking, and heightened strategy.

There were a couple differences with Aldo at his new weight class. Namely his even better head movement (I will reference the Yan fight until you watch it), counters, feints (i.e. flashing the jab to throw a cross, or looking one way then throwing another) and in particular his leg kicks. Whereas Aldo at featherweight pounded the traditional outside leg kick to the lead leg, at bantamweight he made the noticeable decision to incorporate the more modern calf kick to deaden the leg. Exceptionally noteworthy is Aldo’s apparent disregard to when the opposition threw calf kicks in his direction. One would think it would be a taste of his own medicine, but it was mainly the reverse. Referencing astute MMA analyst Jack Slack, Aldo defended the calf kick in one of two ways. Firstly, instead of picking up the leg in a traditional check, he bent at the knee and swung his lead leg back towards his rear knee, causing his opponent to stumble as their shin cut through thin air. Aldo, by contrast, remained stable, as this check did not require any major shift in stance. Secondly, instead of solely stepping in to the kick and trying to time counters off it, Aldo would pivot (there’s that word again) and turn his back foot out while drawing his lead foot in (both turned shins turned towards the opponent’s kick). This also kept his stance uncompromised while having the potential to damage his opponent’s shin. This is a small detail but a crucial one. The above points are part of what kept Aldo competitive, and allowed him to remain afloat in such a competitive division.

There you have it. The SparkNotes version of Jose Aldo. A consistently elite, trailblazing fighter with a lengthy, illustrious career. A man who was at times written off but never wrote back. I said the same thing with Volkanovski; appreciate the legends while they’re around. Jose Aldo deserves to be in the GOAT conversation. What he has accomplished could span a Netflix docuseries. I wish I could see him walk out to “Run This Town” one last time. Because for so long, he ran this game. The King of Rio De Janeiro. Thank you.