When an athlete possesses the “intangibles”, you just know it when you see it. An artist at work. Language can be a bit too reductionist. Simply watch the person in question and you know this is a star in the making. Much the same could be said about any of the four main fighters from the Fighting Nerds camp, who have taken the sport by storm as of late. Caio Borralho at middleweight, Carlos Prates at welterweight, Mauricio Ruffy at lightweight, and finally Jean Silva at featherweight. Far from being a sport of troglodytes, combat sports at the highest level are incredibly technical and nuanced. The Fighting Nerds are but a prime example of this. Fueled by a literal data scientist, the team operates on the principle that fighting is but another equation to be solved, and that there is a means to untie every knot. Much like writing a proof in mathematics, the coaches and athletes prepare notes and contingency plans like a high-end debate team. In other words, fight smarter, not harder.

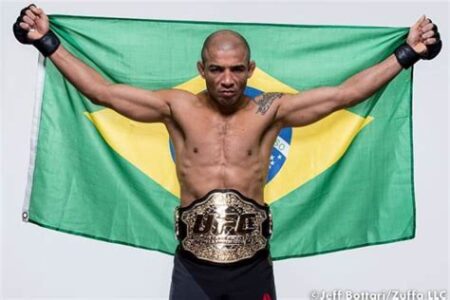

Here, I will narrow the lens on the smallest but most brutal of all the Fighting Nerds. Jean “Lord” Silva. The word “pitbull” is thrown around a lot in MMA, but Silva embodies it in every sense of the word, from his actual proclivity for barking to his fighting tactics. A force of nature at featherweight, Silva is reminiscent of a young Jose Aldo with his speed, power, and overall athleticism. Besides sharing a couple of similarities with Aldo which I will get into later on, they are similar in the fact that at this stage in their career, they both somewhat rely on their physical attributes to win their bouts. That is not to say Silva is a lumbering ogre, far from it. His style simply emphasizes his strengths and his shocking creativity when it comes to violence. Bursting onto the scene on Dana White’s Contender Series in September of 2023, Silva has improved dramatically in a short time frame. Let’s look at Silva’s tendencies thus far in his UFC career, and what has made him such an unstoppable force with plenty of firepower to boot. Important to note, this is not an entirely comprehensive overview. That would turn into a whole senior thesis. This will simply be an analysis of the most common tools in Silva’s arsenal.

It is most prudent to begin with stance first. Every fight starts on the feet, and a fighter’s stance dictates how they will attack and defend. Silva, like others in his camp, tends to stick with an upright, wide base, not unlike featherweight Conor Mcgregor. He is heavy on his lead leg, typically in an orthodox stance, although he will switch to southpaw and has seen success doing so to land combinations. His hand placement changes quite a bit to reflect what he wants to attack or defend next. Silva can often be seen with his hands low, like his teammate Ruffy. At first, this looks foolish and fundamentally incorrect, as his arms are not in position to defend attacks. Yet, for every con, there is a pro. Strikes with his hands lowered are not as easily telegraphed. Plus, Silva often defends strikes at the edge of his range by pulling his head back. He is not as vulnerable as he appears. Watching his fights, he seems like a weed rooted in the ground. He remains heavy on the front leg, his feet firmly on the floor. His body is upright and angled backward, and he can easily pull his head back to avoid high kicks and hooks. It almost looks as though he is playing limbo by how he avoids strikes. Silva dodges punches by pulling and subsequently landing damage, and does so to great effect in every single fight.

To elaborate, Silva’s head movement is not solely used for defense, but to help set up what comes after, that being his counter attacks. A plain example of this tactic is during his very first fight under the UFC umbrella, his Contender Series contest with Kevin Vallejos. I like this bout in particular because it is the only occasion in Silva’s UFC career where the fight went the full 15 minute distance. Thus, we can actually observe more strategy instead of Silva just finishing the fight inside one round. Here, Silva is somewhat raw. His opponent, Vallejos, was a better technical striker who became overwhelmed by Silva’s power. In this fight, we can observe some of Silva’s traits that he carries over to the present day. Same wide stance where Silva leans back, almost like the Notre Dame Leprechaun, pulling back to avoid hazards. The beginning of the first round for Silva reminds me of Petr Yan. It is a feeling out process where Silva is generally more inactive, using the first minute(s) as a litmus test to measure distance and get reads on his opponent. In this matchup, Silva found himself backed against the fence at first, with his opponent being the instigator. After the first round, things change. Silva, having obtained the data he needed, becomes more aggressive. He advances forward, keeping his hands up in a high guard, which is particularly useful against straight punches. This allows him to be in position to absorb shots as he looks to land offense of his own. A third pattern we see in terms of Silva’s stances is somewhere in between. Silva, like the aforementioned Aldo, uses his lead left arm as a post or jab, while keeping his right arm by his chin or up high around his head. Rehashing my Aldo article, the left post serves as a barrier to keep the opponent at bay, allowing Silva to dictate pace. Subsequently, the right hand guards the head as insurance. Unlike Aldo, Silva leaves it at that, he does not take the extra step to pivot out and around as he retreats. However, he often doesn’t need to, as he has a counterpunch already on the way. Here, the left arm serves as the sword, while the guarded right arm is the shield. Silva uses his left arm as a post, or uses it to paw as a jab to measure distance. We saw this against Bryce Mitchell. Mitchell, annoyed at this obstacle, attempts to bat it down multiple times as he becomes frustrated.

Silva is also entertaining in the way he reflects another fighter with the same surname, the great Anderson Silva. Anderson was unorthodox in how he was in perpetual motion, flashing around his arms as though he was doing “air karate” as Joe Rogan put it. While looking a little silly, this made Anderson unpredictable and difficult to read. Jean copies this template. It is not so much strategy as it is gamesmanship, Jean loves to “big brother” his opposition. As he has them retreating, he seems to mock them, moving his hands all over the place, looking like he is about to play pick-up basketball. This show of bravado confuses the opponent while also making him unpredictable.

Silva also employs something I don’t see too often that I am particularly excited to touch on, the use of the double post. This appears like mostly gamesmanship again, as Silva enjoys taunting and playing with his food. Yet, it serves a tactical function. Here, Silva lines up his arms with his opponent’s wrists towards the edge of his range. His hands are outstretched, and he looks as though he is trying to grab the other fighter’s hands. Besides serving as a deterrent (as the opponent now has to work around these posts, while Silva is in position to defend), it also allows Silva to manage distance and land strikes. By “holding” his opponent’s hands, Silva can more or less align his defense and offense with them, like a choreographed dance. His hands are in position to suppress the line of fire. For instance, if the opponent tries to fire a jab, Silva’s hand is right there to block. By contrast, this helps Silva land his own strikes, since he is already basically within range and this allows him time to study what his opponent is trying to do. One of his favorite weapons to incorporate at this range is a step in elbow, which he may throw even without the double post. Elbows are traditionally utilized at close range or in the clinch. Silva, however, finds success using this technique to land these downward-slicing step in elbows at punching distance.

Below, Silva is shown using the double post to land a step in elbow on Vallejos.

Along this avenue, we all know that Silva is a knockout artist and finisher. His best strikes come by way of counters. This distinguishes him from just a simpleton, as in order to do this he needs to have excellent reflexes and distance management. As mentioned, Silva loves to retreat backwards and pull his head back. Once he has his reads right, he will set up a counter, almost always a check left hook. This is usually done when the opponent throws a straight strike (as Silva can pivot around it) and/or is advancing forwards. Prime examples of this are during his fights with Westin Wilson, Charles Jourdain, and Drew Dober. In his bout with Wilson, Silva absolutely demolished him with his counters and striking prowess. As Wilson lunges in (huge mistake when facing Silva), Silva immediately times his check left hook to drop him. This happened numerous times during the entire (albeit short) fight. Wilson would throw a 1-2, then would be clipped by Silva’s left hook. By lunging in, fighters fall right into this trap. Silva did nearly the same exact thing to Dober during their lightweight bout in a more recent fight. Dober, with a stubborn refusal to adapt to the check left hook, fell victim to it again and again, like a bull facing a matador. The Dober fight was the best example of Silva’s counters at work, because Dober made it so damn easy. Dober very obviously telegraphed his strikes and charged in with reckless abandon. In this fight, we see the check left hook as the opponent throws straight strikes, but it is also evident that Silva can time hooks off of a variety of punches. For instance, Dober is countered with a left hook as he lunges in with a right hook, and is also countered with a left hook as he throws a high kick.

In this video, Silva’s check left hook is at its bulldozing best against Wilson.

The above is more or less the bare bones in terms of Silva’s game on the feet. He is large for the weight class, and holds a noticeable speed advantage over nearly everyone he fights, a prime example being against Dober. Silva is not a volume striker, and tends to wait a couple of minutes, or even a full round, to really turn his offense up. That is all he needs, as he can end a fight with just a punch or two. His head movement keeps him out of immediate danger, while his left hook punishes those who get too close. He is sneaky and cunning, and can often be seen faking his opponents out to elicit a reaction, then punishing them for it. A true Fighting Nerd, he sets up traps as bait, using his trademark creativity to keep them guessing. In the below video against Vallejos, we see remarkable sophistication out of Silva, even in his early career. As he advances, he switches stance to southpaw. He then fakes the left hook to cause Vallejos to raise his guard on the right side. Vallejos, focused on the left hook, is wide open to a right uppercut to left straight combination from Silva. Picasso with punches.

When he is not countering, he still throws everything with murderous intent. There is no “point fighting” with Jean Silva. He is constantly circling, reading his opponent’s defense. When advancing, he seems to favor both body and high kicks. As he has his opponent alongside the fence, everything is fair game. Diverse with his shot selection, the finish can come from anything. Hooks, crosses, elbows, or even a right uppercut immediately after escaping a takedown (vs. Jourdain). Like I said, Silva is not stupid, he is ingeniously lethal and will attempt anything, no matter how unconventional. He does not need everything to be technical when he possesses such force and speed, particularly when his opponent is on the retreat.

Two more sections I unquestionably need to hammer home when discussing Silva at this juncture; takedown defense and potential weaknesses in his game (plus how he minimizes them). First on the chopping block, defensive grappling.

When game planning against a fighter, one naturally wants to eliminate their strengths while exploiting potential weaknesses. In the case of a man with boulders in his gloves like Silva, it would be natural to assume that the way to best him is by taking him down, despite the fact that he possesses a black belt in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. After all, few would want to stand and trade with such a menace. The sentiment can be understood, as Silva’s upright stance and backwards-facing posture should make a takedown easier, no? While it is true that he tends to find himself facing single-leg takedowns due to how far in front his lead leg is, it is not that easy. Specifically, Silva has mastered the down block, and different variations of it. When his opponent attempts a takedown, usually the single leg, Silva sprawls backwards and puts his bodyweight on top of his opponent. He can push his left shoulder down into his opponent’s neck/chin, using that left arm to push the head away, in a traditional down block. This forceful, painful barricade is effective at keeping his opponent from reaching his hips. Silva can apply the down block with his forearm as well, or simply post on their head like he is cupping a basketball. Silva’s raw strength makes this motion even more effective. His right arm, in all of the above cases, remains completely free. He can post on the ground if the opponent is indeed able to complete the takedown. Alternatively, he can use it to push his opponent away if his left arm isn’t enough on its own. The most exciting and violent option is using the free right arm to land uppercuts and elbows. He truly can have his cake and eat it too. This relatively noncommittal setup also converts easily to underhooks and other styles of defense. We can see why he must be such a frustrating fighter to defeat. Not only can he effectively defend takedowns from such an upright stance, but he can do it one handed, and cause harm at the same time.

In the below two videos, we can observe different iterations of Silva’s takedown defense. In the first video, Mitchell’s takedown is completely nullified as Silva sprawls and applies the down block, then spins towards his opponent’s back. In the second, as Jourdain is deep on a single, Silva posts his left arm on Jourdain’s head while landing elbows from the top with his right.

The second component to Silva’s defensive wrestling comes when he is pressed against the cage. Here, there is nowhere to go, but that does not make the down block less effective, just adjusted. As referred to in the above paragraph, the down block can convert to an underhook(s) to bring the opponent back to their feet to prevent them from entering the hips. Another option, and a more entertaining one, is to go for the finish with the ninja choke. We all recall Silva’s highlight reel ninja choke finish against Mitchell, one of the premier grapplers in the division. The thing is, this is not the first time Silva has tried it. He has attempted it several times in his last three fights: at least twice against Dober, and twice against Mitchell. It is one of his favorite weapons to implement when cageside. The ninja choke, in my opinion, is a more secure, safer submission to use in this scenario. When trying a guillotine against the cage to punish a takedown attempt, the move is either risky or does not have a high success rate. The guillotine is not the most stable of submissions, particularly when squished against the fence. If the opponent escapes, and there is a good chance they will, you may have now put yourself in a worse predicament (particularly if the bout goes to the ground). So, how does Silva establish this ninja choke?

Using his left forearm and shoulder to dig down into his opponent’s head/neck area, Silva blades his stance and turns into his opponent. What is great about this setup is that the other fighting is actively pushing in to him to try and complete a takedown, so their neck is not difficult to get ahold of. Since they are doing this part of the job for him, it is rather simple for Silva to use the blocking left arm to underhook the head, then use his free right arm to connect his arms on top. Grabbing his right bicep with his left arm, Silva has now fastened his grip in a vice. Unlike jumping guillotine, Silva maintains the high ground, can fully use both arms to apply the choke, and obtains a tighter hold. The thing is, even if it isn’t successful, Silva can always just go back to square one and either try again or defend another way. A high-reward, lower risk choke.

In these two photos, notice how Silva’s blocking left arm converts to an underhook around the head, allowing him to set up a ninja choke against Dober and Mitchell.

In terms of weaknesses, Silva has few. We have established that he is a precise, powerful striker who is rarely held down or threatened by submissions, even by those who are elite on the ground. Like any fighter, he is not perfect. It is important to not be a fanboy prematurely. Silva looks like a world beater, but he is still new to the UFC and yet to face a top ten talent. He is a fine fighter but is prone to recklessness, and does not currently possess the fight IQ of a veteran. He is often seen talking to the ref or corner, taunting, trying to touch gloves with his opponent, or otherwise showboating when he should instead be focused. Showboating is part of what makes him popular, but it is best not to overdo it, he can’t afford to play with his food when faced with a championship level opponent. Additionally, his stance, while it works, is still somewhat risky. The down block is effective, but sometimes it’s best not to tempt fate by leaving the lead left leg out for so long. Is this doable against a man like Aljamain Sterling, or Movsar Evloev? Perhaps. Again, Silva’s wild nature could be his undoing here, as he will go for punches and elbows instead of committing to defending the takedown. It has not come back to bite him…yet. Moreover, being planted on the front leg means he is far easier to target with low kicks to that leg. What little success Mitchell had in their fight came off of oblique kicks and low kicks, which he threw plenty of times to the open target, though not with much power. Also, Silva, whose bread and butter are counters, is not immune to being countered himself. Mitchell, for instance, waited for Silva’s counter left hook so he could level change and attempt a takedown. People notice his tics just like any other athlete. Much of this is simply me nitpicking. Silva is inhumanly durable. I have never seen him genuinely rocked, and he has surprisingly solid defense given his somewhat wild style. As we have covered, he is never as open of a target as he appears.

To conclude, Jean Silva is a potential champion in the making. Like most diamonds, he perhaps just needs some polishing. Like his alter ego, lord assassin, he is a bona fide sharpshooter. His opponents find themselves in a gun fight against a man wielding a larger rifle. Silva is exactly what the featherweight division needs. A gunslinger who can actually handle himself on the ground. His next couple of fights will reveal further data on how he handles himself versus stiffer competition. Every dog has its day, and his is coming.